“History is made and preserved by and for particular classes of people. A camera in some hands can preserve an alternate history.”

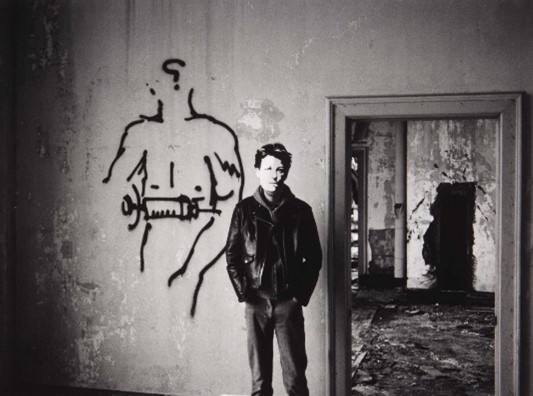

David Wojnarowicz

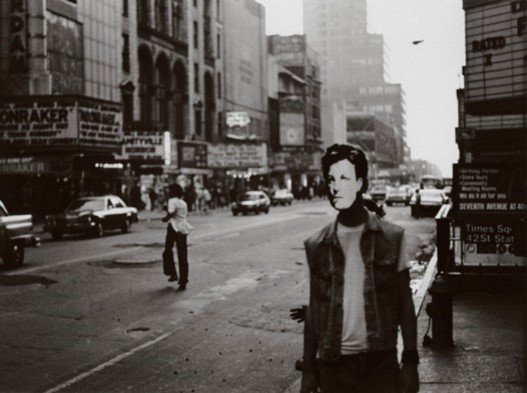

A sort of mythical aura often seems to surround the idea we have of New York until the 90s, before it turned into the glassy and hypermodern city it is today. The images we see when we think about it then, indeed, are not those of skyscrapers and glamorous neighborhoods – but of graffiti everywhere, the sultry and dangerous streets near Times Square, the Chelsea Hotel of the Beat poets, rock musicians and extravagant artists, the drugs, the silvery and buzzy factory of Andy Warhol and so on. If it is so, I believe, it is mainly thanks to the outstanding activity of the young photographers of those years,who managed to transform the ignored and despised subculture of the period into the symbol of an era.

Political images

Taking a photo is never a neutral act – it is most fundamentally about choosing, choosing what to include and what to exclude in the frame of your lens; it is because of this that the famous art critic John Berger used to say that photographs speak more of what is absent than of what is present. This means that shooting can never be an apolitical act: when you take a photo, you’re not only recording a moment in time, but also acknowledging the existence of a certain reality – while possibly disregarding others; its subject is not directly altered or interpreted, as it happens with the other forms of figurative art. Photography speaks of truth: this is why it is so powerful; this is also why it can be so easily manipulated to orient thought.

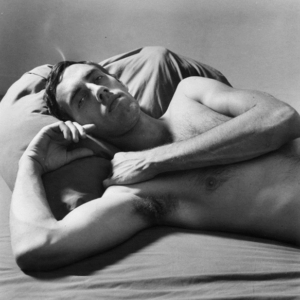

Man in Central Park, 1969

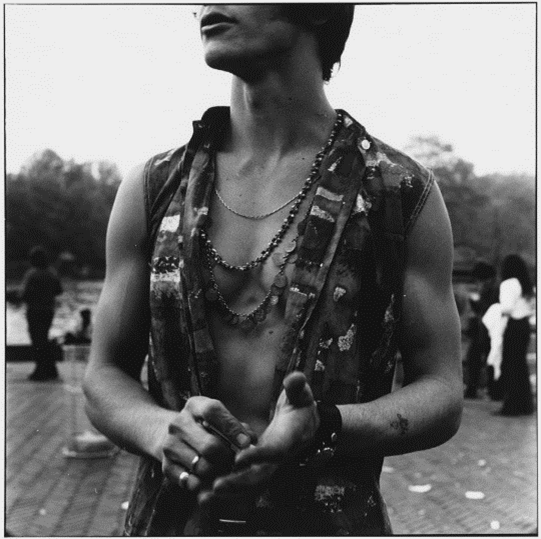

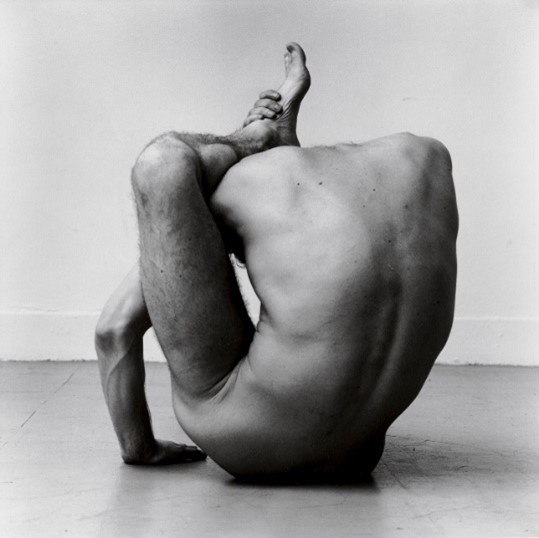

Gary Schneider in Contortion, 1979

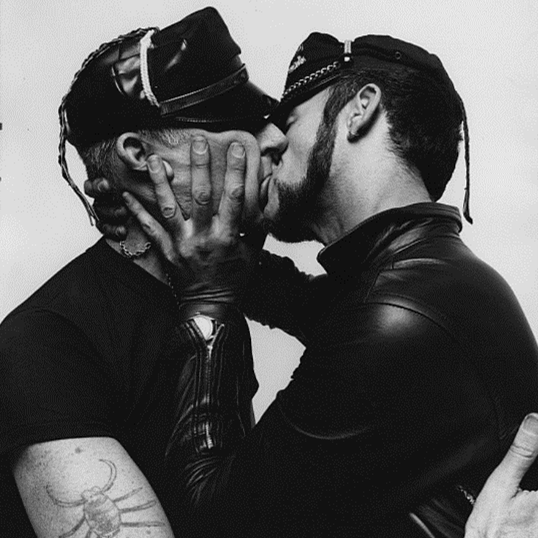

Peter Hujar, Two men in leather kissing, 1966

The protagonists, the themes and the polemics

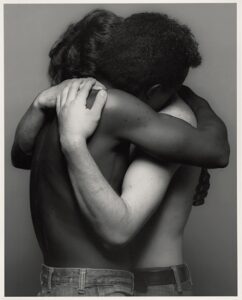

If photography was chosen as the main and most powerful means of expression of those years, it was on one hand because its circulation was easy and relatively cheap – and it didn’t necessarily require the support of famous art galleries sustained by politically-driven national funds; and on the other, because it was a way of providing visual evidence of the plural and extremely diverse creative environment of the time, which didn’t fit the traditional and conservative canons at the basis of the public distribution of images of the time. The works of New York photographers from the 70s and 80s represent very often minorities, marginalized communities and of a youth in the wake of the sexual liberation occurred in the 60s and early 70s. Some of the most appreciated among them – Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, Nan Goldin,Robert Mapplethorpe – focused in particular on the portrayal of the New York queer community, to which many artists belonged, and on the theme of the body, represented in its simple and naked beauty either in isolation or in its encounters with other bodies. If these photographers are still so popular today, with prominent galleries organizing retrospectives on their work and major fashion brands arranging collaborations (see Supreme’s work with Nan Goldin, or the very recent partnership between Zara and the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation), it is because they still appear to us as bold and contemporary experiments, honest and gentle even when explicit – the same motives for which, at the time, they were often considered scandalous and obscene. One of the reasons why these artists started to gain resonance was in fact the many controversies with Christian and conservative associations, often very influential from a political point of view: they contested galleries and museum using of public funds to stage exhibitions of their work, seen as immoral and even pornographic because of its sexual and homosexual content.

Photography against invisibility

Soon, though, there was more to it than the simple necessity to immortalize a certain cultural and creative environment. Photography came to be a political choice on the personal and collective level – as it is beautifully explained in an essay by David Wojnarowicz, one of the great artists, photographers and gay activists of those years, entitled Never doubt the dangerousness of the 12-inch politician. “I wonder” Wojnarowicz stated, “how many people understand what it means to grow up in a society where one is invisible. I wake up every day and if I turn on the television set or look through a magazine or look at the billboards or look at political candidates or go to the movies, I see no representation of my sexuality. […] As the owner of a camera, I am in direct competition with the owners of television stations and newspapers; I can speak with photographs about many different things that the newspaper owner is afraid to address because of agenda or political pressure, or because of advertisers’ dollars. I can make photographs deal with my sexuality and I do because I know that my sexuality is purposefully made invisible by the owners of the various media”. And this was more than just a matter of representation, because people’s attitudes, ideas and votes had started to depend more and more on the limited and manipulated pictures that were delivered by the media: photography hence could be a means of fighting the information control and propaganda performed by the centers of conservative power, that portrayed society as totally white, middle-class and heterosexual.

The AIDS years

The urge to make art deal with politics increased dramatically with the advent of the AIDS pandemic in the 80s and 90s: the government and the politically influenced media not only refused to acknowledge the existence of a diverse society, but also denied to provide fundamental information that could prevent the contraction of a lethal virus and funds for research centers to look for a cure. President Reagan did not speak about the topic for six and half years, and his director of communication became famous for his ridiculous homophobic remarks and publications. This was what the media reported to spread news about the illness, reinforcing dangerous stereotypes and discrimination among the mass audience. People started to die by the thousands, with public and private institution at first denying them treatment fearing they were contagious; as perfectly explained by writer and journalist Susan Sontag in her essay AIDS and its metaphors, the virus came to be considered a sort of moral punishment for the “perverse” behavior of gay men, trans women and drug addicts, which made up for the majority of the infected. In such a context, art as an alternative and effective vehicle of information and a testimony of injustice became a matter of survival. Wojnarowicz explains this necessity very well in the same essay: “Breaking the silence about an experience can break the chains of the code of silence. Describing the once indescribable can dismantle the power of a taboo. To speak about the once unspeakable can make the INVISIBLE familiar if repeated often enough. […] As an adult, I realize if I make something and leave it in public for any period of time, I can create an environment where that object acts as a magnet and draws others with a similar frame of reference out of silence or invisibility. To place an object that contains what is invisible because of legislation or social taboo into an environment outside myself makes me feel not so alone; it keeps me company by virtue of its existence”.

David Wojnarowicz: the silence that kills

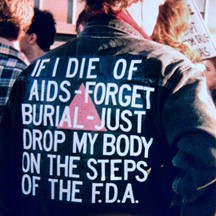

Wojnarowicz died of AIDS in 1992, at age 37. The last years of his life were completely dedicated to political and creative activism: he started to collaborate with the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) movement, and for a march he realized a jacket with the words “IF I DIE OF AIDS – FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.” (which actually happened: a few months after his death, ACT UP organized a political funeral on a vast scale in Washington, with hundreds of people scattering the ashes of their loved ones, Wojnarowicz’s included, on the lawn of George Bush’s White House). There are two particularly remarkable and moving works of his from this period though, in my opinion.

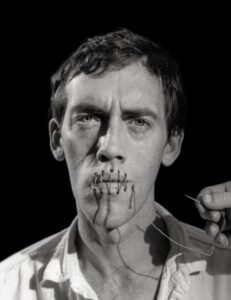

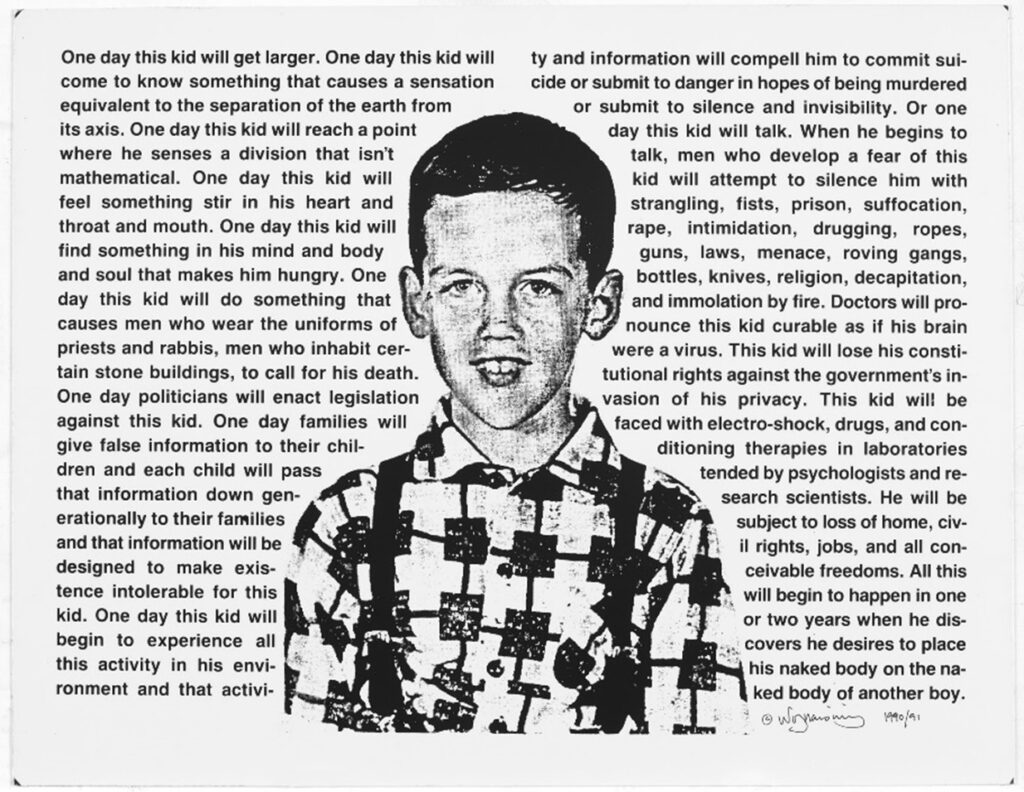

The first is entitled “Silence=Death”, as the ACT UP’s motto, a self-portrait with his mouth sewn by stiches, blood dripping from his chin and eyes appalling in the message they convey: the silence imposed on people by the prejudice, discrimination and taboos of society on one hand, and the silence imposed on the media by political and religious powers on the other, were causing a massacre. The second is perhaps the most meaningful and powerful work of his artistic production. It pictures an enlarged photograph of Wojnarowicz as a child – a symbol of all the children who struggle to find their place in a world which doesn’t accept them for what they are, and that will face some kinds of hatred, injustice and oppression for the rest of their life, then as now; he is surrounded by the following words:

I love these two works because I think that in their bare but imposing simplicity they manage to break that code of silence Wajnarowicz mentioned in his essay – as they just cannot leave the viewer indifferent. They remind us of the power that the media can have on the life of people and the importance of mediatic inclusivity, especially now in times when every attempt to enlarge representation is discredited as “political correctness” or “cancel culture”. And they are evidence of the cardinal role art plays from a political, social and, I would add, human point of view. Because in times of populism, conservative propagandism and information control – what is art? Art is anti-propaganda.