On modern musical imperialism and the West’s problem with labeling non-white music

Written by Stambekova Aida

Perhaps you remember the hot statement Tyler, The Creator made at the 2020 Grammy Awards right after winning the Best Rap Album for his debut record, IGOR.

“It sucks that whenever we — and I mean guys that look like me — do anything that’s genre-bending or that’s anything, they always put it in a rap or urban category. I don’t like that ‘urban’ word — it’s just a politically correct way to say the n-word to me,” the singer said, highlighting the way his album was miscategorized.

Tyler’s comment about how the Western, or more specifically, the American music industry loves to categorize all music made by black artists as “urban” regardless of their true genre seemed to put the final nail in the coffin. As the Recording Academy CEO, Harvin Mason Jr. has expressed in an interview to Variety, the term has been a “hot button” for a while. The discussion around the term was exacerbated further by nation-wide Black Lives Matter protests in response to police brutality and the rise of white supremacist sentiments. The Grammys’ ruling body made some changes throughout the nominations later that year. Among those, the contentious category Best Urban Contemporary Album was renamed to Best Progressive R&B Album.

However, Tyler was not the only artist to speak about the intentionality behind placing non-white music under one or two broad categories, usually outside of the main pop ones. In 2017, Frank Ocean made the decision to not submit his album Blonde to the Grammy’s as a protest against racial imbalances in major categories like Album of the Year and the overall misrepresentation of Black artists. For years, not only Black but also Latin and Asian music has been heavily separated from the “white music” nominations. Artists like Burna Boy, Bad Bunny, Rosalia, and K-pop’s biggest act BTS have spoken out about the ways in which major music awards do not yet know how to properly categorize non-English music. For decades, the promise of “crossing over” into Western recognition has been held upon artists as a sign of success. But when that crossing only reinforces old boundaries, are we really moving forward or just crossing over to nowhere? Let’s talk about it.

“Race records” vs “Hillbilly music”

The origin of harsh separation between “American” and “foreign” music can be traced back to the beginning of the commercial music era in the 1890s. Prior to any race-based divisions, early commercial recordings like cylinders and discs were classified based on the source of sound. Instrumental types would include categories like cornet solos, piano solos, or duets, while voice types would include categories like female and male solos.

In the early 20th century, musical genres were the clearest mirrors of social hierarchy: opera’s increase in popularity and tightly-targeted advertisement as “serious and noble” made it music for the elites. Simultaneously, the only categories that explicitly nodded towards social division were linguistic categories – songs sung in Spanish, French, Mexican, Turkish – aimed at marginal groups beyond the white middle class. And just like that, the industrialized urban America was divided into three groups: the educated elites that bought the opera music, the respectful middle class that enjoyed the band music, and the hyphenated Americans who remembered the home land through ethnic records.

The post-World War I world brought a technology that changed the music industry once and for all – radio. Radio meant free music and no need to change records every few minutes, thus encouraging the industry to broaden its audiences. The first “race records” series was launched in 1921 by a recording label called Okeh, in an attempt to market Black musicians specifically to Black listeners. Following Okeh’s success with the race series, Black musicians were now recorded by big and small firms, with a regularity never seen before, albeit not integrated into the mainstream. Later, Okeh reinforced the separation by marketing rural white music as “old time tunes” and “hillbilly music”, the latter name derived from a popular band The Hillbillies. Both hillbilly and race records were assumed to be marginal to white, urban, and middle class music.

The incentive behind separating foreign and white music is said to be mostly business-driven. Because the general markets were segregated, companies would orient separate music catalogs to stimulate phonograph, disc, and sheet music sales. J.A. Sieber, an advertising manager at General Phonograph Corporation that owned Okeh, has said: ‘‘About three years ago colored people were considered mighty poor record buyers, and cash visits by colored customers were rare and far between. Then came the original race records issued by our company, and the fallacy that negroes [sic] would not buy records was completely put to rout. […]” The same happened to “ethnic records”, sung in Spanish, Mexican, Yiddish, Italian, and other languages, that were primarily sold in ethnic shops and rarely reviewed in the same press as mainstream white records.

The Great Depression hit the music market just as it did any other aspect of life: sales were extremely low and many recording labels were either gone or acquired. The total number of categories dropped by nearly a third, with race records and foreign language records being first in the line to be cut. The further development of race and hillbilly records was separate just like it initially started: the former developed into rhythm and blues music, while the latter got labeled as western and country music.

As the Jim Crow segregation laws continued to tear up the society, racial music categories were seen as common sense. Moreover, they became a guideline for aspiring artists that seeked to be noticed and recorded by big labels: white musicians who did not sound “white” enough or African-American musicians who did not sound “black” enough both had difficulties with getting promoted. The term “race records” persisted up until 1949, when Billboard renamed its Race Records chart into an R&B chart.

Rock & roll and the continual musical segregation

Despite the marketing divide between “race records” and “hillbilly music”, the musical traditions in America never existed in isolation. In the 1950s, blues, gospel, jazz, and country fused into a brand new genre – rock & roll. Born in Memphis, a city shaped by African-American migration and vast cultural exchange, the genre was largely pioneered by Black artists like Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Fats Domino, Big Mama Thornton, Big Maybelle, and many others. The music scene grew more integrated, with white artists entering the Billboard R&B charts, but despite all that, the system quickly found a way to capitalize on original singers and writers of rock & roll.

Said capitalization was started by Sam Phillips and his Memphis Recording Studio, known as a launchpad for a huge number of white rock & roll artists including Elvis Presley. Phillips was a businessman who quickly realized that to compete with major records at the time, he needed white artists. Following Elvis’ breakthrough, Phillips kept on pushing the idea of making “white boys sing like black men”.

Producers from other major labels followed suit, buying songs from Black musicians and re-recording them with white artists to target larger pop audiences. Black artists, in contrast, were kept under smaller and independent R&B recording labels. Denied access to major producers and exposure, they were unable to enter pop charts and get guaranteed radio play.

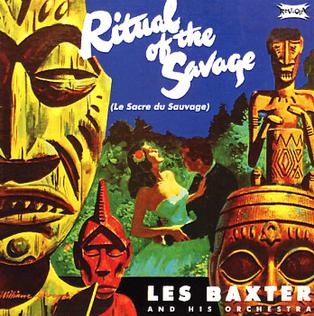

Similarly, Latin-American rhythms like rumba, mambo, and bossa nova gained more traction, but mostly when interpreted by white artists. Popular became “Exotica” records – records that simulated tropical, non-native, pseudo experiences of Oceania, Southeast Asia, Hawaii, the Caribbean, and tribal Africa. Recorded by white artists, they fetishized “foreignness“, while excluding the true native artists. Even popular European records – French and Italian – were framed as “continental pop” and not mainstream pop.

“Urban” and “world” music

In the 1970s, the American music industry kept on insisting on drawing a clear boundary for what counted as mainstream white pop. The controversial term of “urban” music was coined quite accidentally: a legendary radio DJ and director Frankie Crocker created the term when establishing a new WBLS radio station in New York. He used “urban” to encompass the inner-city sound that was ruling the club scene of the period: specifically disco, funk, R&B, Motown, and the early instances of rap music.

The term, although coined by an African-American music industry insider with a good intention in heart, soon became a lazy way to describe any Black-originated music. By confining vastly different genres – often associated with “hood” aesthetics – into one box, it has created a way for white executives to neatly package and advertise Black music to a broader audience. Up until 2020, all you had to do to be considered for an “urban” category is be a Black artist making any “Black music” genre, and it didn’t really matter what kind of music you were making. The term built a wall between white, “true American” music, and “urban, hood” Black music. And while numerous white artists drew from disco, soul, R&B, and hiphop for their own careers, they were not considered “urban.”

While the American music industry was satisfied with the wide usage of the term “urban music”, another term to describe foreign records has emerged. In 1986, an American singer-songwriter Paul Simon released Graceland, an album where he sang English lyrics over tracks performed by black South African bands. The album was harshly criticized for appropriation and more importantly, for breaking the cultural boycott on South Africa for its apartheid regime. One year after Graceland’s huge success, “world music” appeared as a new commercial category, blurring all “local music from out there” as one, broad division, peripheral to Western (British and American) music.

The usage of the term was contested, revealing its questionable character. What was considered as “world music” largely depended on the political and geographical context. Reggae or salsa, due to their popularity and substantial ethnic populations in the US, for example, were never categorized as “world music”, while in Britain they were. In Singapore, when distributed by western companies and aimed at western audiences, “traditional” Asian music like Canto-pop, J-pop, and Chinese Opera was labeled as “world music”; meanwhile when distributed by Asian labels, these genres were put under mainstream sections.

Both “urban” and “world” music terms got cemented in the industry in the 1980s and 1990s, and eventually lingered through the 2000s. In 2020, in response to backlash, when Best Urban Contemporary Album was being renamed, the category for Best World Music Album was also rebranded as Best Global Music Album.

Categories translate into biases

The continuous segregation of foreign music, although the industry is slowly moving towards proper inclusion, translates into biases and prejudices towards talented artists who lie outside of the conventional white pop norms. Streaming platforms and global charts may have blurred strict national and racial categories, but the division still exists, replicating the good old hierarchy of “English pop center” and “Non-English niche periphery”. These labels worsen the skewed perception of non-Western artists as mere representatives of “other” cultures rather than musicians with strong global achievements that often surpass white pop artists. The recent conversation around the 2026 Super Bowl halftime show that culminated in a petition to remove Bad Bunny in favor of a country singer George Strait further proves a point that for the American music industry, national and racial labels prevail over musical substance. When anything Black becomes “R&B and Rap”, anything Korean becomes “K-pop”, and anything Latin becomes “Reggaeton”, the question of whether the industry is allowed to keep filtering artistry through “otherness” comes as a natural conclusion. When access to mainstream airplay, media coverage, and “big and important” award nominations are halted for many talented non-white and non-pop artists due to the division of “Western” and “Global” music, the idea of musical imperialism does not sound so absurd anymore. When a non-white musician’s global success is framed as “crossing over”, the notion of the West, and specifically America, preserving center legitimacy in the music scene becomes not a relic of the past, but a reality that dictates the criteria for success and who gets to claim it.