When visiting a museum, there are two types of people you can observe. Those who know their way around the exhibitions and are engrossed in conversation about a piece and others who meander around trying to look engaged but their blank faces give them away. However, both types of visitors are battling the same two forces – the relentless human need to derive meaning from our experiences and our aesthetic sensibility that urges us to be still and be with the art around us.

In this article, our writers Fabio Ferrara and Isha Induchudan walk you through the artistic and psychological interpretations of art in contemporary society with the aim to provide our readers with a comprehensive guide on how to approach appreciating art.

Art, artists and viewers

With the first statement, the art historian Ernst Gombrich introduced in 1950 one of its most well-known works, “The story of art”, a book almost specifically designed for the public to be read, to help most people to appreciate and understand in a simple, clear and straightforward manner.

With this statement, also, he redesigned the role of the artist and of art in its contemporary society.

Art gets to be no more a thing done to please others, rather a masterpiece of the creative genius of the artist that expressed itself through the line, the colour, the form.

However today, almost 100 years later we seem to move backwards. We are stuck in an exhausting quest for conclusions in our oversight to art. We try so hard to find meaning in objectively identifiable elements in a painting;

the experience of a red circle in an abstract composition seems to be replaced by the metaphors we associate to it.

A fun example of this necessity in finding an emotional connection with the image is given to us by one of the masters at the Bauhaus school in 1920, Johannes Itten.

The teacher asked its students to analyse and copy the weeping Mary Magdalene from the Grünewald Altar, but commenting the results of his students Itten exploded at the sight of the mere copies of the artwork made by the class.

If any of them had an artistic sensitivity, he shouted, when faced by such a powerful depiction of weeping they would have cried themselves, felt the weeping of the entire world, instead of “just redrawing it”!

Mind’s Search For Meaning

To answer this question, we can look to the brain and how it creates meaning in the world around us. Looking at the literature, a clear pattern emerges; our perception of reality seems to be driven by a subconscious drive to explain rather than to experience.

The earliest records of human communication have been documented in the form of cave paintings, inked tools and other devices which historians posit were used to bring tribes together. The visual symbolism of these artefacts was not established for aesthetic purposes but rather to organise and forward information to the tribe. Research conducted by linguists Miyagawa, Lesure and Noberga discusses that some of the earliest records of cave paintings have been strategically located in chambers with high acoustic echoes, suggesting that these locations were key informational exchange junctions for our ancestors – which furthers the idea that visual symbolism from its origin, was established as a means to transmute information.

Besides messaging to the tribe, visual communication in its earliest form served as a means of storytelling. Anthropologists, Moody and Laurent worked with American Indian tribes in the 80s and through their studies, discovered that storytelling was the prime method through which the tribe organised themselves. Aside from oral recitation, important norms and rules were visually documented as a reference to future generations. We can see the corollaries of this in the “Theory of Narrative Thought” (TNT). Beach and Bisswell showed that neurologically, the brain collects sensations and organises them as events.

These events are then sequentially arranged in order to predict the future from events of the past. The role that images then play in storytelling can be understood in a similar manner. Every image is perceived by the brain as a collection of sensations that are then arranged to depict an event that must be related to one’s knowledge of the world.

Heart’s Search For Meaning

During the centuries several modes of artistic interpretation and ways of seeing had been adopted. The main problem has, nevertheless, always been between the content and the form, that is: what it is represented in an artwork and the way in which we perceive it.

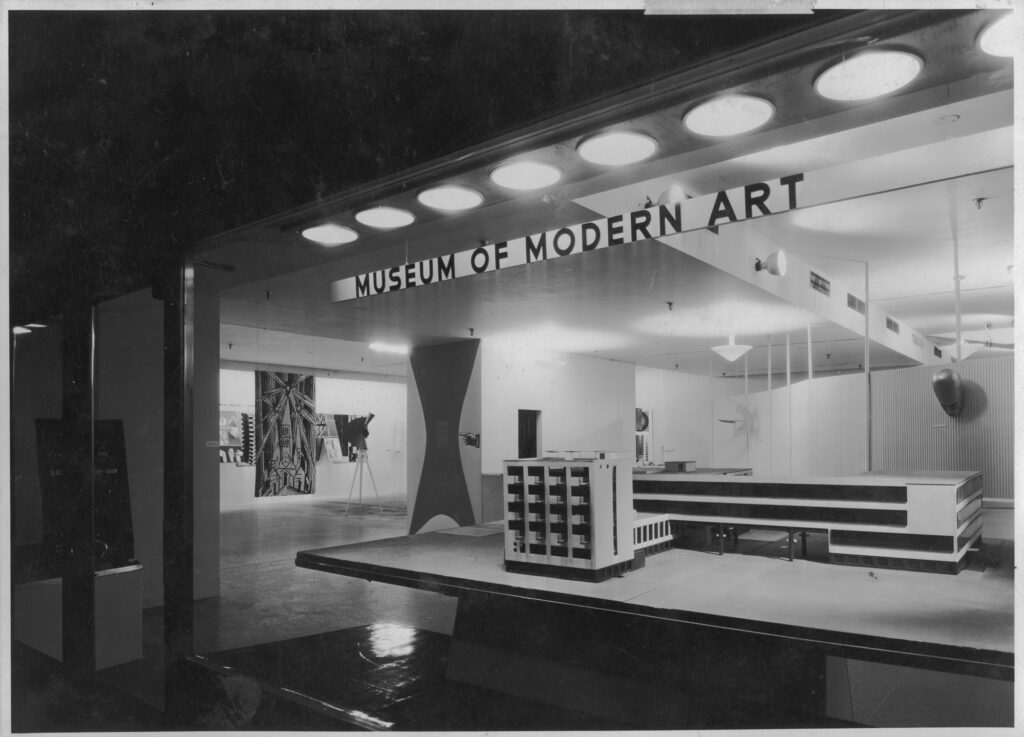

Museums are more than often seen as containers of artworks, and artworks as containers of information. The “experience” of the museum, as well as the “experience” of the artwork is merely given by the curatorship of the masterpieces, rather than from the masterpieces themselves.

While it is true that the human brain may feel obliged to create an interpretation of what a museum symbolises, the aesthetic joy you experience when viewing a piece of art is undeniable.

Most crucially, we can understand this in the concept of embodied cognition in cognitive sciences. While the focus for the previous arguments comes from a top-down approach of mind over matter, embodied cognition instead asks, “how does the body affect the mind”. Christopher Tyler, director of the Smith-Kettlewell Brain Imaging Center discusses how we experience art through embodied cognition.

When viewing the painting “the birth of Venus” many report feeling as though they are floating in the seashell with Venus herself.

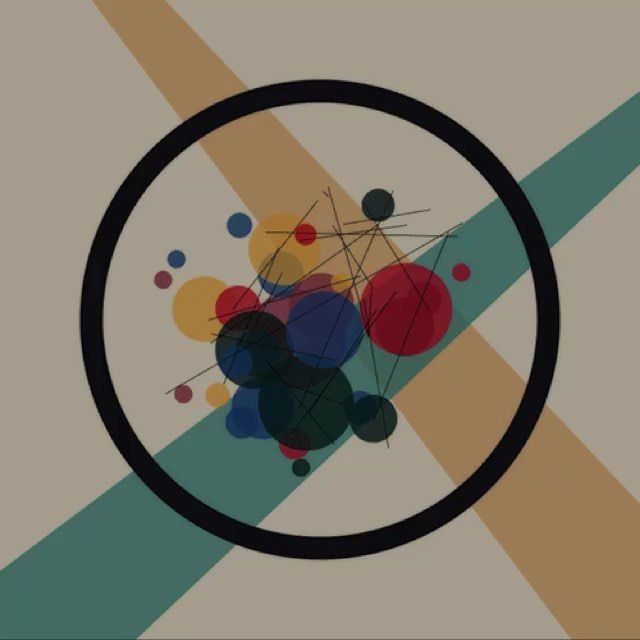

The Russian painter Vasilij Kandinskij translated this concept into the artistic matter while writing in 1910 its famous book “Concerning the spiritual in art”. In the book, the artist explains how colour, both in a painting and in reality, can trigger our spiritual awareness of this fourth dimension.

More specifically he says that colour can have two possible different effects on the spectator: a “physical effect” based on momentary impressions and a “psychic effect” based on our emotional response to the painting itself, towards which the colors are able to reach our soul.

Therefore, a little bit philosophically, the colour is capable to elicit emotions not because of the way we associate it to something else, rather for its own spiritual nature.

How Can One Experience Art?

The true validity of Kandinskij’s writing is not up to us to say; what we can say, about this experience of oneness with a painting can more colloquially be recognised as mindfulness: a state of mind where one calmly acknowledges the present moment and any bodily sensations, allowing the traffic of the mind to come and go. The practise of mindfulness has its roots in Buddhist tradition and through Western research into the benefits of mindful habits, they have made their way into mainstream lifestyle. A study conducted by graduates from the University of Tennessee showed that across age groups, those who engaged with the visual arts (either through observation or creation) reported higher scores of mindfulness. Not only were participants able to appreciate the artwork presented to them more, but they also reported a greater sense of inner mental satisfaction. This demonstrates that by allowing yourself to be present, it is possible to overdrive the brain’s urge to create meaning and appreciate artwork as an experience.

Our brain seems to interact with art in two ways, one way that is driven by the search for meaning and the other is through experience. This then begs the question, how can we detach from the pattern-seeking drive of the brain and choose to be present with patterns of the piece in front of us?

Museological narratives are currently trying to cope with this theme, presenting more often than not their artworks in thematically organized rooms or displays. The creation of narratives, rather than the historical catalogation of paintings, might help the viewer breaking free from systematic categories of interpretation. That is:

challenging the viewer with new interpretations to historical events, new ways to understand an artwork, new possibilities to stop in front of a specific painting to actually look at it.

However, this method is not always quite enough, and if it is true that a good curatorship can radically influence our experience of a museum and of a painting, the other side of the coin is that getting informed on how to look at a painting and how to visit a museum is essential for visitors.

In 2004, the American art historian and critic James Elkins tried to suggest a “practical recipe” for museum visitors, proposing an 8-step guide to fully try and enjoy the experience of a painting:

- Go to museums alone

- Don’t try to see everything

- Minimize distractions

- Take your time.

- Pay full attention

- Do your own thinking

- Be on the lookout for people who are really looking

- Be faithful. Once you’ve spent time with a painting, promise yourself you’ll come back to see it again.

It is, of course, not complete and not enough to just rely on this list.

Yet, by underlining the importance to go to museums for the experience of the artwork, we will allow ourselves to feel the most intimate and native encounter to the artwork, for only then, only after having cried in front of it, dissect its elements into knowledge of historical value.