Written by Livy Li

After the phenomenal success of the film Kim Ji-young: Born 1982, I went to read the novel. On Japanese Goodreads, many people gave it four stars. One highly upvoted review said:

“A thin book, just over a hundred pages, sparsely printed and written like a diary without any literary flair. Hardly well written. Its popularity isn’t surprising—it probably resonates because it lists, in chronological order, all the frustrations Korean women have faced since childhood. If you have a friend who never reads or knows nothing about gender issues, give this book as homework.”

That’s how people who don’t understand fiction read it. Kim Ji-young: Born 1982 is a sociological fiction.

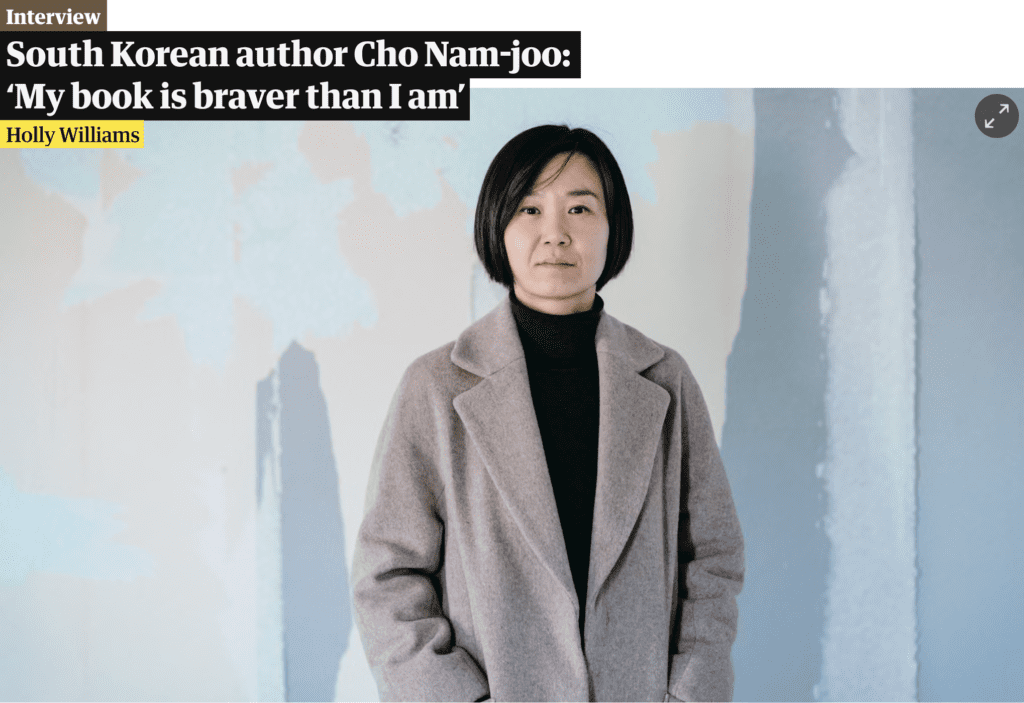

The author Cho Nam-joo (b. 1978) graduated from Ewha Womans University with a degree in sociology and spent years writing for current-affairs programs. She has said that her goal in writing this novel was “to record, without distortion or belittlement, the real lives of women living in Korea.”

That’s why Kim Ji-young must be the most ordinary person imaginable — the smallest prime factor of Korean womanhood. She cannot have any special personality, any special looks, any special experiences; she cannot even be more sensitive than average, because the moment her emotions are described in lyrical detail, her suffering would seem self-inflicted, as if she were just hypersensitive and easily bruised.

Cho Nam-joo’s innovation lies in the way she moves between the concrete individual and the abstract type, portraying a person who, drifting through life, has accumulated countless wounds — someone distilled from qualitative data yet never reduced to a mere concept. The control required to achieve this is astonishing, which is why so many ordinary readers felt such an overwhelming shock.

After that, I read Kim Ae-ran’s Summer Outside (비행운).

If Parasite is a movie you can smell, Summer Outside is a novel you can smell. Her narrative power is astonishing, sometimes even more vivid than cinema, as if she manipulates the finest sensory threads of reality itself.

“Suddenly a boiling current rose to my throat. The feeling hit like rain in a desert. I realized that because I am alive—or while I am alive—someone, somewhere, is in pain because of me, someone I may or may not know. The realization was physical, an upheaval of being that had nothing to do with love.”

“I opened the window, folded the blanket. Turned the water heater to warm. Let out the day’s first stream of urine.” —The joy of existence itself.

“A square of sunlight slanted across the linoleum. Within that square something faintly rippled—the shadow of a drifting filament, the spring air quivering beneath my feet. I suddenly exclaimed, thrilled: ‘Ah, even invisible things have shadows.’” — The delight only the happy can feel when their senses open.

“Myeong-hwa realized the words she spoke were not her ancestors’ tongue but the ‘language of laborers’ used by migrants. She grasped the breath summoned by accent and tone, and gradually understood that even death cannot perfect the texture of a foreign language.” — A Chinese Korean woman working in South Korea.

It’s terrifying. Traditional realist or socially critical novels give readers a kind of safety. Whether it’s Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, or Flaubert, the reader knows the life on the page belongs to someone else; the writer’s unit of description is the individual. Even though there are shared experiences, resonances, and empathy, there’s still a skin between us and them. However bad things get, we can still say, after all, it’s someone else’s problem.

Kim Ae-ran, on the other hand, writes existence itself. She makes you suddenly realize: so this is what my being actually feels like. She writes about the material particles and relationships that make up your life — the air pressure, temperature, and force you feel every minute.

It’s over. Kim Ae-ran is a bad woman, and by the time you realize it, it’s too late. Her prose isn’t a comfortable chair you can sink into — it turns the everyday into something uncanny. Her pen seems to pierce down to the atoms of matter, so the transformation is absolute and irreversible. The water that felt safe a minute ago becomes another, more threatening substance — looks the same, but inside it’s changed.

And this “alienation” isn’t really alienation at all — just as every sci-fi or zombie movie is ultimately about the present, making the unspeakable aspects of our reality visible: poverty, survival under pressure.

Dazai Osamu’s No Longer Human has been called “a book in which everyone can recognize a part of themselves.” I’ve never quite agreed. But Kim Ae-ran’s humanity can truly make you cry, because the unit she writes about isn’t “the person” but the atom of the person — and before you know it, she’s writing about you.

She writes these fragile, insignificant lives in their incurable decay, utterly powerless as they are crushed by the world. A body that is rotting and being ground down feels the pain, feels fear; and we had already been dragged into the nerves of these trampled individuals; we are forced to confront the entire process, unable ever to return to a normal, fake life we once had. If ants or cockroaches were conscious, what kind of world would they perceive? And if we can’t perceive the full reality of our own existence, how are we any different from them?

Kim Ae-ran’s prose cuts like a blade. She has sparked my fascination with the collective power of Korean women writers. Stimulated by her work, I found Questioning Minds: Short Stories by Contemporary Korean Women Writers, translated and introduced by Yung-Hee Kim, Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at the University of Hawaii.

It turns out that behind Kim Ae-ran and Cho Nam-joo lies over a century of women’s fiction. The first wave of female Korean writers appeared in the 1910s, just as Japan annexed Korea and the Joseon dynasty ended. Perhaps it was the turbulence of national collapse, perhaps colonial rule loosened the Confucian shackles on women, perhaps Western learning arrived through Japan—whatever the cause, in 1917, a 21-year-old girls’-school graduate named Kim Myeong-sun (1896–1951) published the first short story written by a Korean woman.

Kim Myeong-sun was the daughter of a wealthy businessman and his concubine, a former courtesan who had left the trade. Both mother and daughter suffered under the cruelty of the legitimate wife. Because of this background, Kim became the target of gossip at Hansŏng Girls’ High School and dropped out at fifteen. In 1913, she went alone to Japan to study at Kōjimachi Girls’ School, but returned to Korea before graduating, finally completing her education in 1917.

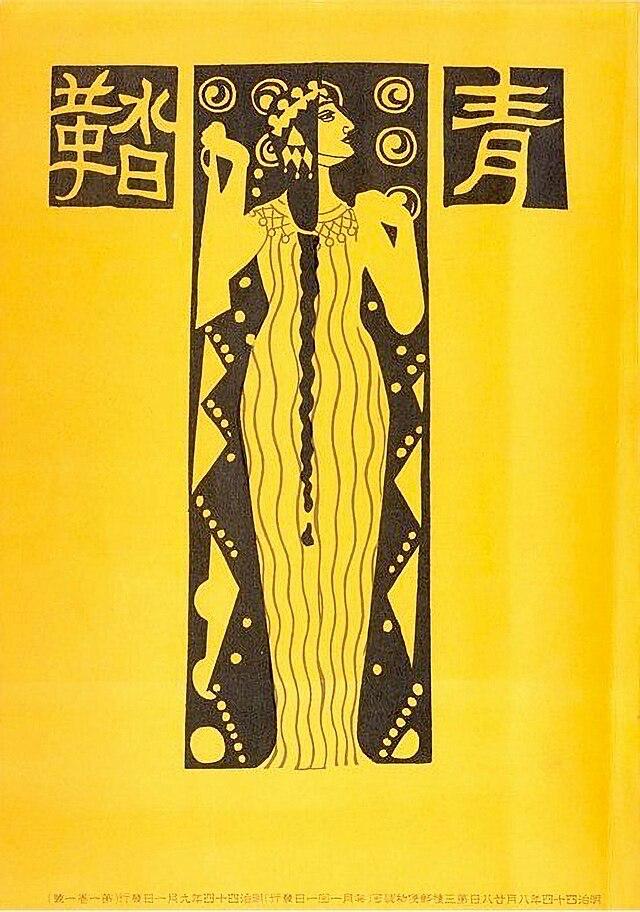

Her interrupted schooling didn’t stop her talent from shining. That same year, her short story Dubious Girl (의문의 소녀) won second prize in Youth (Ch’ŏngch’un) magazine and was hailed as the true beginning of modern Korean literature, opening a new chapter after Korea’s premodern tradition. In 1918, Kim went back to Japan to study literature and music, joined progressive artistic circles, went back, wrote prolifically, and joined theater groups. In 1925, she published The Vault of Heaven (창궁; 蒼穹) — the first book ever published by a Korean woman writer. She also passed the civil service exam to become a reporter for the Daehan Maeil Shinbo, making her one of Korea’s first professional journalists.

But Kim’s interests turned toward performance. She entered the film industry and starred in at least five movies — a risky field that could ruin fortunes. By 1932, her literary creativity had dried up, her finances had collapsed, and she reportedly considered selling goods on the street to survive. Between 1932 and 1935, she is said to have returned to Japan to study French and music. In 1936, she came home and turned to children’s stories and poetry, but she never regained her literary standing. Her final years were spent in poverty and illness, and she died in a mental hospital in Japan.

During Japan’s colonial rule, Korean writers had to contend with censorship, surveillance of intellectuals, and eventually a ban on the Korean language. Even so, Korean women writers of the time believed that education could free women from hardship and open a path to self-realization.

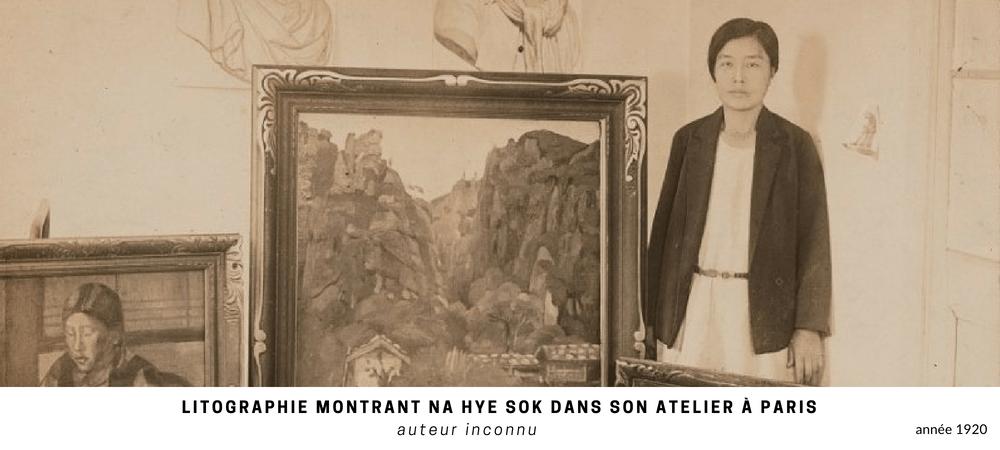

Among the first generation of women writers, the most striking was Na Hyesŏk (1896–1948), who wrote under the art name Jeongwol (정월; 晶月). Her works bore a strong feminist tone.

Na was luckier than Kim Myeong-sun. She also came from a rich merchant family, but was loved by her parents. Encouraged by an older brother studying in Japan, she went there herself after graduating from high school at seventeen to study Western oil painting. It was a time when Japanese women were awakening to self-consciousness; she joined Seito (青鞜), a Japanese feminist literary circle that championed women’s self-expression and intellectual freedom, an experience that would profoundly influence her and her future work. At university, Na served as secretary-general of the Association of Korean Women Students in Japan and edited its journal Women’s World.

In 1918, Na graduated as Korea’s first woman to earn a bachelor’s degree in art and began teaching art at a girls’ high school. But she joined the anti-Japanese independence movement and lost her post. She held solo exhibitions, won awards, and gained national fame. She married a lawyer who had courted her in Japan; later, he was posted as a diplomatic envoy to Andong in southern Manchuria, and she followed. She then traveled with him to Europe and the United States, raising three children, painting, exhibiting, and writing art and cultural criticism for newspapers, as well as fiction reflecting her frustrations in marriage.

By 1932, Na Hyesŏk was arguably the most celebrated woman in Korea. Magazines and newspapers competed to interview her about her travels and worldview. Then came the scandal that shocked the entire nation: Choi Rin, a Cheondogyo religious leader, published an article detailing his affair with her in Paris. Na sued him in a French court for defamation. Her husband divorced her, and she lost custody of her children. Branded immoral, she was barred from public exhibitions, though she managed to live by selling paintings and writing until 1934, when she published her two-part Divorce Testimony (이혼고백서, 離婚告白書) in All Korea magazine.

That piece ignited fury. Na didn’t just reveal the humiliations of her own marriage; she challenged the foundations of patriarchy, discussing women’s suppressed sexual needs and her husband’s unwillingness to confront them, even suggesting that the contentious “trial marriage” idea of the time could prevent such tragedies. After that, no one would buy her paintings, and even her family disowned her. From 1934 to 1936, she survived by writing travel essays for All Korea, sank into poverty, and died quietly in a charity hospital, her name and burial place forgotten.

In popular speech, her name became synonymous with moral ruin: when a girl wanted to study art or literature, parents would scold her. “Do you want to become another Na Hyesŏk?”

In 1974, the publication of the biography of Na Hye-sok, Your Mother Was a Pioneer (에미는 선각자였느니라), finally washed away a bit of the stigma that had been cast upon her.

Yet generation after generation, women writers continued to commit their crimes, refusing to bow to convention or reconcile with their times: Kang Kyŏng-ae (1907–1943), who wrote about poverty and the working class; Choe Jeong-hui (1912–1990), who portrayed the quiet struggles of women as wives and mothers; Chŏn Pyŏng-sun (1927–2005), Yi Sŏk-pong (1928–1999), and Pak Sun-nyŏ (b. 1928), who traced Korea’s historical traumas from the colonial period through the post-Korean War era.

During the 1970s and 1980s, women writers born in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s swept Korea’s major literary awards: Pak Wan-sŏ (1931–2011), Sŏ Yŏng-ŭn (b. 1943), Kim Chi-wŏn (b. 1943), Kim Ch’ae-wŏn (b. 1946), Yun Chŏng-mo (b. 1946), O Chŏng-hŭi (b. 1947), and Kang Sŏk-kyŏng (b. 1951).

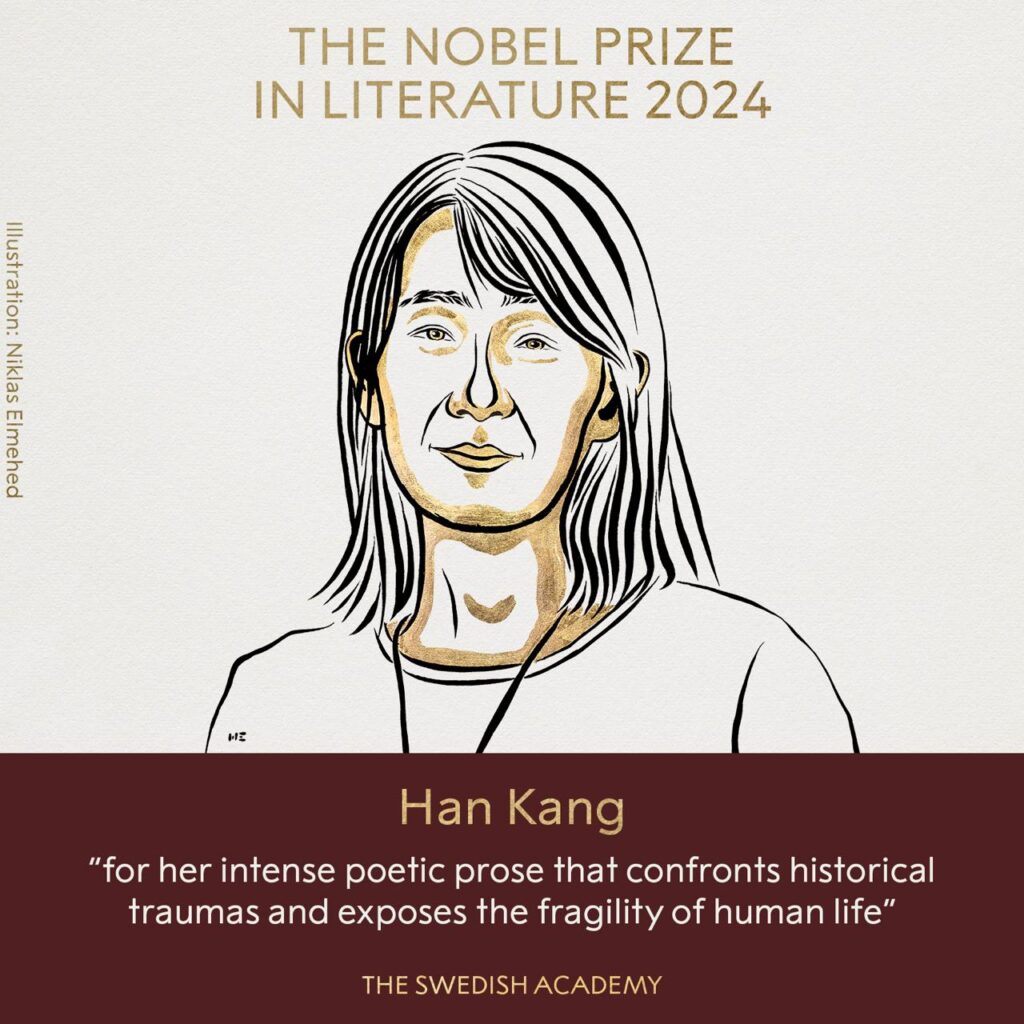

Then came the internationally acclaimed generation: in 2012, Shin Kyung-sook (b. 1962) won the Man Asian Literary Prize for Please Look After Mom; in 2016, Han Kang (b. 1970) won the Man Booker International Prize for The Vegetarian—a novel that eventually earned her the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Korean, and the first Asian woman, ever to do so.

So why are Korean women such good writers? Because they have always felt compelled to show the world how women’s lives intertwine with the transformations of their era. They’ve carried a sense of mission to create. In the end, it’s about backbone—unyielding, unwilling to bend or compromise, and utterly incapable of giving up.

[Read the Japanese version of the article below]

韓国の女性は、どうしてあんなに“書ける”のか?

映画『82年生まれ、キム・ジヨン』が社会現象になったので、原作小説も読んでみた。日本版 Goodreads でも四つ星が多くついていて、ある高評価レビューにはこんなふうに書いてあった。

「100ページ少しの薄い本で、字間もゆるく、内容は日記のように淡々として文采はほとんど感じられない。とても“よく書けている”とは言えない。ただ、売れていることについては全く驚かない。おそらく韓国女性が幼い頃から経験してきた不愉快な出来事を、時系列に沿ってまとめてあるからだろう。本なんて読まないしジェンダー問題にも疎いような人には、入門書として渡すのはありかもしれない。」

これは、小説を「そういうふうにしか」読めない人の感想である。『82年生まれ、キム・ジヨン』は社会学的小説だ。著者のチョ・ナムジュ(Cho Nam-Joo, 1978–)は梨花女子大学社会学科卒で、長年時事番組の放送作家として働いてきた。彼女自身、この本の目的を「韓国で生きる女性たちの“ありのままの現実”を、ゆがめることなく記録したかった」と語っている。

だからこそ、キム・ジヨンは「もっとも普通の人間」でなければならなかった。韓国女性という集合の“最小単位”である存在。際立った性格も、特徴的な外見も、特別な境遇もあってはならない。感受性が人並み以上でもいけない。細やかな筆致で心情を描けば、かえって「彼女が繊細すぎるだけ」に見えてしまい、痛みの普遍性が失われるからだ。

チョ・ナムジュの革新は、この「具体的な個人」と「抽象化された個体」のあいだを絶妙に往復する筆致にある。量的データから立ち上がりつつ、概念上の存在に堕することなく、ぼんやりと日々をこなしながら無数の傷を蓄積していく一人の人間を描き出した。その制御力たるや驚異的で、だからこそ数えきれないほどの“普通の人”に強烈な衝撃を与えたのだ。

その後、私はキム・エラン(Ae-ran Kim, 1980–)の『あなたの夏は大丈夫?』も読んだ。

『パラサイト』が“においのある映画”だとすれば、キム・エランの小説は“においのする文学”である。彼女の叙述力は凄まじく、音や光の助けを借りて作られた映像世界よりもはるかに生々しく、感覚の最微細な領域にまで到達してしまう。

「このライトを見ると、なんだかプロの現場に迷い込んだ気がする」

――大食い番組のスタジオへの印象。

「突然、熱いものが喉元までこみ上げてきた。その感情は、砂漠のど真ん中で遭う驟雨みたいに唐突だった。(略)私が生きているせいで、あるいは私が生きているその時間に、誰かが強く痛んでいる――そんな考えが、暴力的なまでの実感を伴って襲いかかった」

――生死をかいま見た瞬間、遅れて訪れる身体的な悟り。

「窓を開け、布団を畳む。給湯器をぬるま湯に設定する。新しい一日の最初の一滴を放つ。」

――存在そのものへのよろこび。

「四角い陽光が斜めに床にさしていて、その中で何かがふわりと揺れていた。床が映し出した埃の影、つまり足元に漂う春の気配だ。私は思わず興奮して叫んだ。『ああ、見えないものにも影があるんだ』」

――幸福な人だけが受け取れる感覚の開き。

「明花は、自分の話しているのが祖先の言葉ではなく、よそ者が使う“労働者の韓国語”なのだと気づく。(略)死んでも到達できない他国語の質感というものを、少しずつ理解し始める。」

――韓国で働く朝鮮族中国人女性。

恐ろしいのはここからだ。これまで読んできたリアリズム小説や社会批判には、どこか“安全圏”があった。トルストイにせよドストエフスキーにせよフローベールにせよ、結局は「他人の人生」であり、作家が描ける単位もあくまで“個人”である。共鳴も共感もあっても、最後には一枚膜がある。「結局は他人事」に逃げ込める。

しかしキム・エランの描くのは“存在”そのものだ。

――「ああ、私の存在って、こんなふうになっていたのか」

そんな気づきを強制的に突きつけてくる。そこに描かれるのは、生活から剝がし取れない物質の粒子と関係性、刻々と肌で感じている温度と気圧と圧力のダイナミクスである。

もう終わりだ。キム・エランは恐ろしい作家だ。この事実を自覚した時にはすでに遅い。彼女の筆致は、読者が安逸にもたれかかれる安楽椅子などではなく、日常を異界へとねじ曲げていく。物質の原子レベルまで入り込む筆力ゆえ、その変容は容赦がない。同じ水が、前の瞬間には安心だったのに、次の瞬間には脅威に変わってしまう。外見は同じでも、中身ががらりと変わってしまったように。

いわゆる“異化”だが、それは異化というより、SFやゾンビ映画が常に“今、ここ”を描いているのと同じで、現実社会の見えない側面を可視化したものだ。貧困、圧力下のサバイバル。

太宰治『人間失格』が「誰もが部分的に自分を重ねられる」と評されても、私はそこまでとは思わない。だが、キム・エランの“人間”は、読者を本気で泣かせる。なぜなら彼女が描く単位は“個人”ではなく“個人を構成する原子”だからだ。気づけば、私たちは彼女の筆の下に書き込まれてしまっている。

描かれた“草のように小さな命の腐敗”に抗う術はない。外界に踏み潰される個体は、痛み、恐れ、震える。その神経回路に私たちは引きずり込まれ、すべてを直視することを強いられ、もう“普通で虚構の人生”には戻れなくなる。もし蟻やゴキブリに意識があれば、世界はどれほど恐ろしく見えるのか。そして、もし私たちが存在の全貌を感じ取れないのだとしたら、彼らと何が違うのか。キム・エランの筆は鋭い剣のように空を裂き、私は韓国女性作家への集団的な興味を抑えられなくなった。

ハワイ大学のYung-Hee Kim教授が翻訳・解説した『The Questioning Mind:現代韓国女性作家短篇集』を読んでみると、キム・エランやチョ・ナムジュの背後には、100年以上続く女性文学の伝統があることを知った。最初の世代は1910年代――日本による朝鮮併合、李氏朝鮮の終焉の時期である。動乱の刺激か、植民地支配が儒教的拘束を弱めたのか、西洋思想が伝来した影響か、理由は一つではないだろう。1917年、21歳の女子高卒業生キム・ミョンスン(1896–1951)が、朝鮮女性による初の小説を書き上げる。

キム・ミョンスンは富商の妾腹の娘で、母は元芸妓。母娘とも本妻からの虐げに苦しんだ。その出自が漢城女子高で噂になり、15歳で退学。1913年に一人で日本に渡り麹町女学校に通うが未卒で帰国。1917年にようやく学業を終えた。

しかし才能は隠せない。同年、彼女の『神秘の少女』が雑誌『青春』の懸賞で二席を受賞し、朝鮮近代文学の幕開けとされる。1918年に再び渡日して文学と音楽を学び、進歩的文学サークルに参加。帰国後は創作・劇団活動に励み、1925年には女性作家として初の作品集『生命の果実』を出版。さらに試験を経て『大韓毎日申報』の記者となり、韓国初期の職業女性記者となった。

だが、彼女は次第に演劇に魅了され、映画界へ。主演を何本も務めたが、当時の映画産業は莫大なリスクを伴い、1932年には創作力が枯れ、生活も困窮。露店商になりかけたという。1930年代半ばに再び日本に渡りフランス語と音楽を学び、1936年帰国して児童文学や詩に転じたが、文壇の地位は戻らず。晩年は極貧と病に苦しみ、日本の精神病院で亡くなった。

日本統治期の作家たちは検閲や監視、韓国語使用の禁止にさらされながらも、「教育が女性を救う」と信じ、自己実現の道を模索した。

この時代でもっとも輝いた女性は羅蕙錫(ナ・ヘソク 1896–1948)だ。筆名は“晶月”。鮮烈なフェミニズム作家である。

羅蕙錫は富裕な家庭に生まれ、愛されて育った。兄の勧めで日本留学し、17歳で西洋画を学ぶ。当時は日本の女性解放運動が盛り上がり、青鞜社や雑誌『青鞜』の影響を大きく受けた。学生時代には在日朝鮮女子学生会の書記長、機関誌編集も務める。

1918年、韓国人初の女性美術学士となり教職につくが、独立運動に参加して解雇。個展で成功し、留学時代から求婚していた弁護士と結婚。夫の任地の満州へ同行し、さらに欧米へ同行。三児を育てながら絵を描き、文化評論や小説も執筆した。

1932年まで、彼女の名声は韓国女性として頂点にあった。しかし、崔麟との不倫スキャンダルが暴露され、名誉毀損で訴訟を起こすも、夫には離婚され、子どもの親権も失う。彼女の名声は地に落ち、公的展覧会への参加も禁じられた。それでも執筆と絵で生計を立てていたが、1934年に発表した『離婚告白書』が決定的な破滅をもたらす。そこでは単なる私生活の暴露ではなく、性の欲求の抑圧や夫婦関係の不平等、さらには「試し婚」を提案するなど、父権制の根幹を揺るがす内容が書かれていた。彼女の作品は売れなくなり、家族とも絶縁。1936年までに困窮を極め、慈善病院でひっそりと亡くなった。埋葬地も不明。

民間では長いあいだ、「ロ・ヘソクみたいになるな」と親が娘を叱るほどの悪名を着せられた。

それでも、その後の世代の女性作家たちは書き続けた。時代に屈せず、和解もせず。

貧困層を描いたカン・ギョンエ(1907–1943)、

女性・妻・母の日常の抵抗を書いたチェ・ジョンヒ(1912–1990)、

植民地から戦後までの歴史の傷を描いた作家たち、

そして70–80年代には多くの女性作家が文学賞を席巻した。

そして現代、世界文学の舞台に立つ作家たち――

2012年、シン・ギョンスク『母をお願い』がマンアジア文学賞。

2016年、ハン・ガン『菜食主義者』がマン・ブッカー国際賞。

韓国人どころかアジアで初の受賞である。

では、なぜ韓国女性はこんなにも“書ける”のか?

彼女たちはいつの時代も、自らの存在と時代の変化がどう相互作用するのかを語りたいという衝動に突き動かされてきた。常に新しい表現を切り拓く使命感を持ってきた。

つまるところ、骨が硬いのだ。

回り道も、曖昧に濁すことも知らない。

諦めも、後回しもしない。

Sources mentioned:

Yung-Hee Kim, Questioning Minds: SHORT STORIES BY MODERN KOREAN WOMEN WRITERS, Hawaii Studies on korea , 2010