Written by Filipp Beldushkin

I am not really well-versed in the pop culture that is popular among Gen Z, even though I am part of it, so please take my analysis with a grain of salt. I believe the Western civilization is undergoing a major institutional and value crisis. The values of Gen Z and the society’s reality are in conflict with each other. Institutions are becoming more and more inefficient and illegitimate. Potential shocks such as unpredictable advancement in AI (both in terms of labor and financial markets), unsustainable growth in US debt, and large-scale military conflicts threaten to unravel the current status quo and deepen the divisions between Gen Z’s values and the principles on which the current society is built.

Many Gen Z people support Luigi Mangione because there is no way to hold people who are responsible for the failure of the US healthcare industry accountable other than to shoot the CEO of the largest health insurance company. Murder did not change the system, but many people believe justice was served. The US Government should have regulated the health insurance industry to make it work, but it is inept even to pass a budget in time, let alone solve complex issues.

Religion is one avenue for people who grow disaffected with the government and society to find themselves heard. That is, in my humble opinion, why young people are flocking to religion, as you might have read in the news. I myself am a Christian anarchist because I believe true justice is only possible at the Last Judgement. What human societies construct is the necessary evil; some kind of legal system is vital for any healthy community, but it has no authority or possibility to provide actual justice. That is why I believe what Luigi Mangione allegedly did is bad: murder is not a way to get justice.

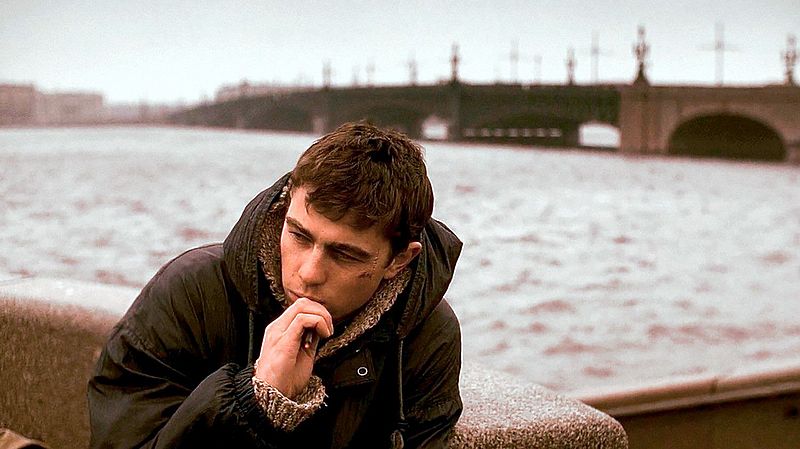

Culture is another avenue for people to channel their dissatisfaction with the situation. Aleksei Balabanov’s films, and especially his Brother dilogy, are infused with the anxieties of Russian people after the collapse of the USSR (I have discussed Balabanov’s masterpiece Of Freaks and Men with other cinephiles here). Roman Mikhaylov is the first Russian cult director after Aleksei Balabanov, largely because he is able to channel the anxieties of Gen Z. His films are very intimate, consciously apolitical, and yet are able to gain popularity among people who are lost in modern society. A Trip to the Sun and Back is a love letter to the lost Gen Z youth of the 1990s, which is also a politically safe way to talk about what troubles the modern Russian youngsters. In music, rap today is the equivalent of rock in the West during the 1960s and the USSR during perestroika, an era of rapid political change in the USSR before its collapse. It is no wonder that hip-hop culture is prevalent in Roman Mikhaylov’s films (one of his upcoming films is about the Russian breakdance underground scene): for example, there is a song called “How much is the money worth?” performed by a Russian rapper Husky in Mikhaylov’s Firebird.

While Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another may be THE movie experience of the year, as pitched by the critics and social media, I think it is also a very wrong movie exactly because of its focus on aesthetics and abandonment of ethics. Meanwhile, his namesake Wes Anderson has found the right mixture in The Phoenician Scheme. As I wrote in my prognosis for this movie, it is very important for an action film to focus on the morality of choices in high-stakes situations and deglamorise warfare, terrorism, and espionage. One Battle After Another makes terrorism look attractive and admirable, while The Phoenician Scheme shows a journey towards God and the simple life of Zha-zha Corda (Guillermo del Toro), an amalgam of enigmatic and megamaniacal Charles Foster Kane (Citizen Kane) and Gregory Arkadin (Mr. Arkadin) in classical films by Orson Welles. Despite Wes Anderson’s trademark multilayered approach to filmmaking, Zha-zha Corda, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), and Bjorn (Michael Cera) are much more relatable to me than any other character in One Battle After Another. Kelly Reichardt is another director who is really great at subverting the action genre: her Meek’s Cutoff (Western), Night Moves (political thriller), and The Mastermind (art heist) are brilliant in how the tension that is usually present in thematically similar movies is dissipated by her focus on the consequences of choices.

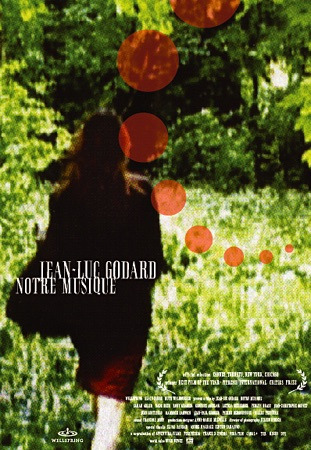

I think any discussion of politics in modern art would be incomplete without talking about Lars von Trier’s Dogville and Jean-Luc Godard’s Notre Musique. These films have shown two polar opposite ways to deal with injustice. Grace, the quintessential “golden-hearted” protagonist so often favored by Lars von Trier, endures systemic enslavement by the residents of Dogville. Upon being freed from her serfdom by her gangster father (from whom she had actually been hiding in Dogville), she orders her father’s henchmen to execute Vera’s (one of the Dogville’s inhabitants) children one by one unless she suppresses her tears, mirroring how Vera destroyed the figurines Grace had bought for herself. An Israeli Olga in Notre Musique, concerned about the injustice Israel inflicts on Palestine, runs into a theater and declares she has a bomb in her bag. Olga encourages people to die with her for Israeli-Palestinian peace, but everyone leaves the theater and she is shot dead by the police. The thing that makes this plot thread so heart-wrenching is that Olga did not have a bomb on her, her bag being filled with books; she is incapable of violence, yet dies in such a violent manner, misunderstood in her suicidal attempt to help other people who are supposed to be her enemies as an Israeli Jew. In these two movies, both Grace and Olga are initially “golden-hearted”, but while Olga uselessly tries to stop the endless cycle of violence, Grace ends up perpetuating it, becoming a part of the problem herself.

Since I am talking politics in art, I cannot help but mention Tom Lehrer, a famous American musician and mathematician. Tom Lehrer’s satirical songs are direct on very sensitive topics like nuclear proliferation, BDSM, and the fetishism of violence in media, yet they aren’t vulgar. In other words, his songs diagnose the society’s illnesses and resonate with me a lot. Tom Lehrer does not offer solutions to them, nor is it his job as a satirist. Neither does religion. What religion has to offer is guidance on how to live your life to save your soul. All of Tom Lehrer’s songs were released by him into the public domain and are available here.

As a conclusion, here is my message to myself and fellow Gen Z people: throughout the socioeconomic and geopolitical storms, it is necessary to overcome them with as little harm to the body and soul as possible, to make this metaphorical “trip to the Sun and back” without getting burned by it. There is a need in a real world to find some middle ground between the fictional characters of Olga and Grace. It will be hard, but it is possible.

P.S. I am currently working on a film that would hopefully offer a visual dimension to his songs based on the principle of synthesis between sound and image in the spirit of Dziga Vertov Group. I have already finished approximately 25 minutes of it, and if you are willing to collaborate, please feel free to contact me. My email for contact regarding collaboration on the film: filipp.beldiushkin@studbocconi.it