The bolder the art style, the bolder the politics

Avantgarde and revolution, Socialist Realism and Stalinist ideology, innovation and perestroika

That of communist Russia has doubtlessly been a troubled and traumatic journey, and it has been more than thoroughly documented through the very tools of propaganda that fueled its unravelling: posters. Posters were cheap to print and distribute to the masses, at a time where mass communication was otherwise impossible. They were immediate, emotionally charged, and easily comprehensible in nature, thus representing the perfect vessel for the paradoxical marriage of utopia and manipulation that characterized the early decades of the Soviet Union.

The art styles of these powerful images, much like the power structure and ideological expression of the Soviet Union itself, did not remain constant, but rather changed radically according to the message’s needs.

Revolution and Avant Garde

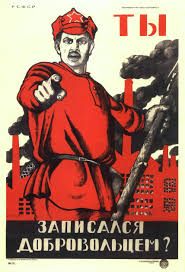

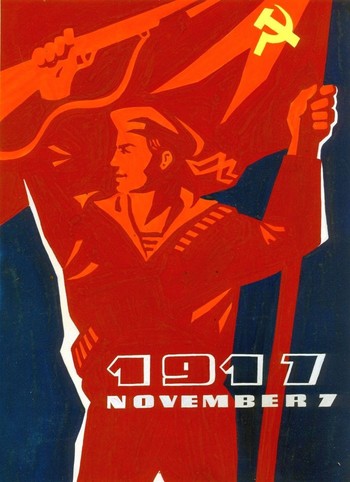

The Bolshevik Era (1917-1921) was an extremely prolific time for propaganda posters: thousands of separate designs, plastered all over occupied towns and battle fronts, called for revolutionary action in the civil war against the Whites. The style at this time was extremely expressive and direct, with witty and exhortative slogans, bold shades of red, and the early adoption of revolutionary symbols like the red star and the hammer and sickle that have become synonymous with the Soviet experience.

Both this period and the subsequent, relatively more relaxed, NEP (New Economic Policy) Era (1921 – 1927) were characterized by optimism and progress, which were embodied by the development of the artistic current of Constructivism (represented by painters such as Malevich, El Lissitzky, and architects such as Vladimir Tatlin) and its omnipresent influence on poster art itself.

The abstract, geometric style of constructivist art rejected the sophisticated conceptualization of bourgeois art. Rather, it attempted at translating the theme of collectivism, central to the Soviet narrative, into the visual exemplification of simple shapes united by geometric harmony. Much like the newly united proletariat, the squarest and triangles utilized by these artists represented a part of something greater and powerful.This period was characterised by an effort towards increasing literacy, as most citizens did not know how to read and could only rely on visual cues, with defining works such as “Alphabet of the Red Army Men” by caricaturist and cartoonist Dimitri Moor, which set the lexicon and grammar of Soviet propaganda to come.

How Stalin ruined Soviet Propaganda Art

The First and Second Five-Year Plans (1928-1937) were Stalin’s attempt at transforming the Soviet experiment into a fully industrialized communist power. This led the People to collectively shift their efforts towards lending their labor to the new industries, rather than to the now obsolete revolutionary struggle. As a result, the first Five-Year Plan still carried on with jarring, photo collage posters representing the heroic struggle of this effort, but things changed drastically as this style was quickly replaced by a far more prosaic Socialist Realism.

The Kremlin had declared that Suprematist and Constructivist art styles (with their abstract shapes and experimental nature) were too “intellectual”, “elitist” and bourgeois, which implied deadly consequences to any artist that still subscribed to the Avant Garde. On the other hand Socialist Realism was embraced (if not explicitly designed) by the party, as the ideal instrument to push the narrative of the “great, powerful, idyllic industrialized Soviet Union”, its unmatched achievements, and its wise, strong, and hard-working leaders. It should be noted that it’s in this period that the personality cult of Lenin and Stalin was truly instituted.

The airy, gentle brush strokes of Socialist Realism painted an idealized Russia that granted its viewers a -possibly misplaced- sense of security and hopefulness, which completely replaced the urgency that had thus far characterized the Soviet propagandist narrative. There no longer is a true call to action in its original sense: the previously revolutionary proletariat is now being asked to be an obedient and supportive witness to the rise of an authoritarian power, which was in charge of that progress that previously belonged to the abstract “collective”. The myriad of hands from the 1930 poster “Working Men and Women – Everyone to the Election of Soviets”, by Gustav Klutsis, now have names, and that bright red optimism has a specific face.

Where ideology lacks, the art… gets blurry

After a brief revival of the Bolshevik poster during the Great Patriotic War -as WWII was known in the Soviet Union- (1939-1945), the Early Cold War saw a reinstatement of Socialist Realism. During this period this style maintained its idealized, compulsory, and artificial visions of the Soviet Union, and the celebration of the figure of Stalin. The narrative was that of an optimistic post-WWII recovery, reliant on its leader, and fierce of his vigorous economic programs, the consolidation of the Soviet Bloc in Eastern Europe, and the development of the Atomic bomb.

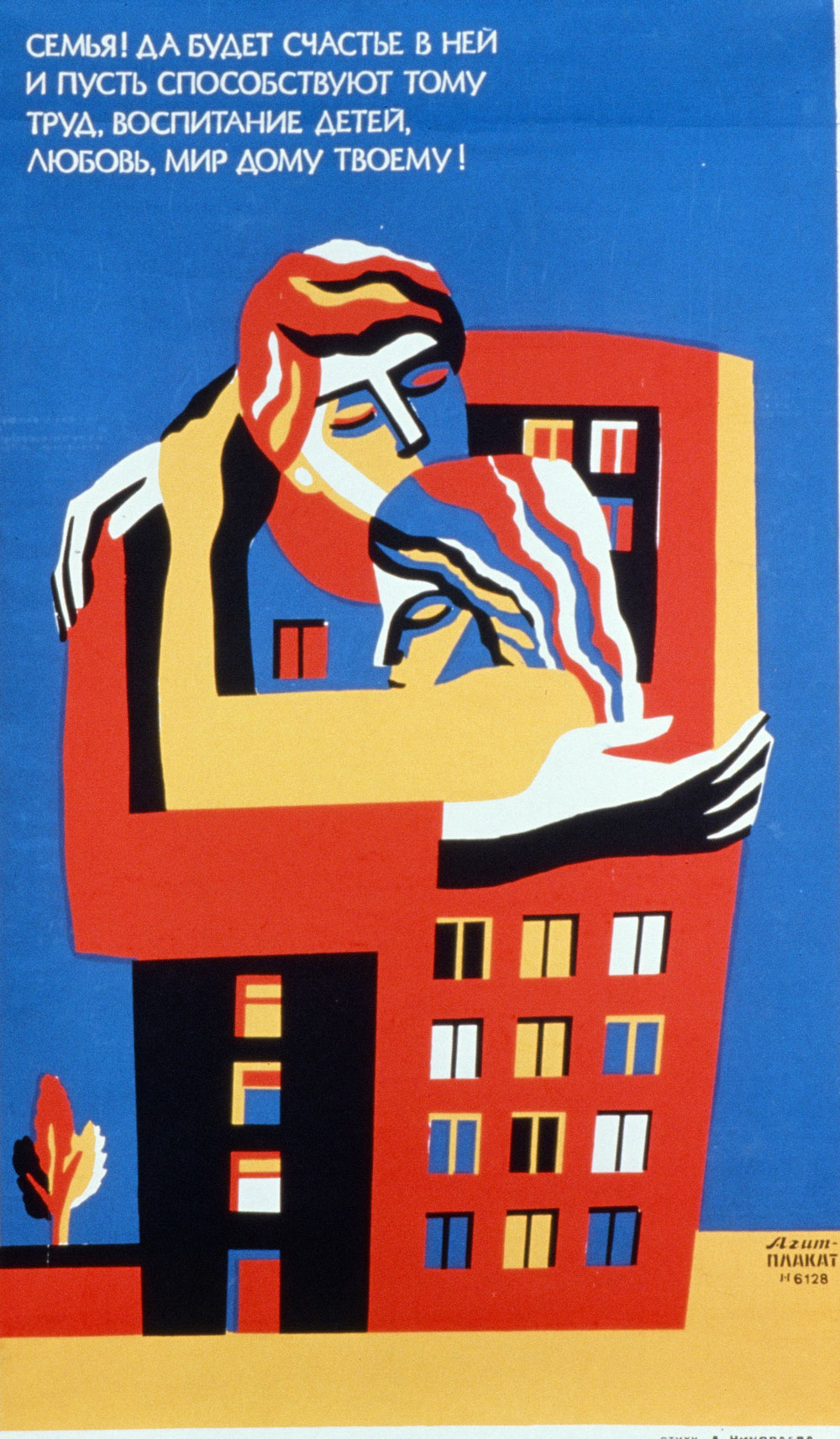

TheThaw Era (1954-1963) and the Economic Stagnation Era (1964-1984) saw a stagnation in artistic language despite the atmosphere of political uncertainty that reigned after Stalin’s death in 1953. Socialist Realism was still being enforced as the mandatory art style, as its comforting and positive aesthetic was seen as a safe enough way to handle the de-Stalinization process on the propagandist front. There was however a loss of that extreme idealization that had characterized this artistic current thus far, especially in the depiction of industrial realities, shifting between grotesquely happy and enthusiastic workers, and artworks revealing the harsh reality of industrialized Russia, such as “Young Steel Workers” by Bevzenko, with its representation of child labour and the harsh work conditions of steel factories. Finally, as Soviet control became weaker outside of Russia, more stylistic contaminations and experimentations were able to take place, generating an unprecedented diversity in the visual language of the Soviet Union and, consequently, in the possible narratives to be told.

Innovation and Perestroika: winds of change in art and politics

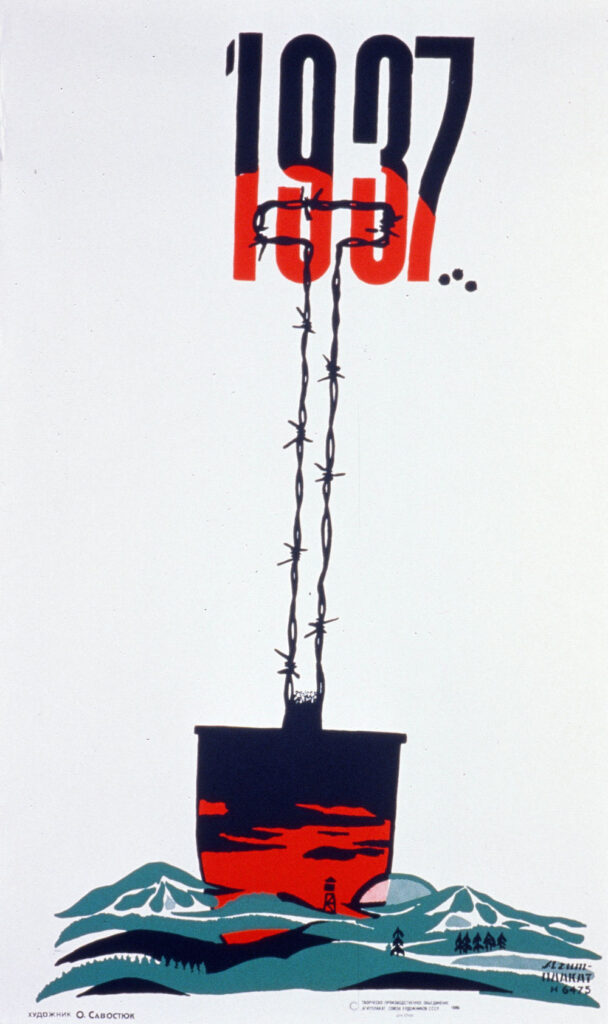

It wasn’t until the Perestroika Era (1985 – 1991), with Gorbachov’s talks of openness (a.k.a. glasnost) and economic reprise, that new air was breathed into the Soviet propagandist visual language. The population’s malcontent was palpable, the economic situation was inching closer and closer to its complete collapse, and the desperate need for change that spread through the nation resulted into a “diversity and exuberance that had been absent from Soviet design for many decades”, as wrote Steve Heller in his introduction to the 1989 San Diego exhibition “Poster Art of the Soviet Union: A Window Into Soviet Life”. This exhibition was organized with the help of Oleg Savostiuk, secretary of the Union of Soviet Artists, who collected and curated a series of 75 posters designed from 1986–1989 by union members, thus offering a direct insight into the current political and social discourse in the Soviet Union.

Imagery varied from realistic painting, to photographs, to cartoons, to highly graphic and stylized interpretations, text was also (though a few fonts still dominated the scene) much more diverse, and print relied heavily on colourful offset lithography which still -of course- privileged the colour red. Subject matters ranged from celebratory, to informative, to now -perhaps for the first time- critical, with topics like glasnost, defeating bureaucracy and Stalinist reactionaries, alcoholism, and disarmament with the US.

This newly experimental wave of Soviet design was truly symptomatic of the oncoming liberation and emancipation of the Soviet People, with this artistic freedom as a predecessor to the actual freedom that was to come.

With much more brightly colored hues, experimental interpretations of the real onto the visual, and a critical eye, members of the Soviet Bloc were ready to embrace the change that was to come with the fall of the Union: a time of self-determination and the redefinition of the meaning of being a citizen and a Nation.

The boldest art style, for the very boldest political sentiment.