The towering skyscrapers of Garibaldi and Citylife attempt to cast a shadow over an emerging crisis gripping Milan. The ever-present sight of those sleeping on the streets exposes the harsh realities of wealth disparity and xenophobia haunting both the city and Italy at large. A sight almost as common as Aperol Spritz and all-you-can-eat sushi: in the parks, in metro stations, under any roof that they can manage.

Italy is a developed nation in the global north with a high standard of living, for those who can afford it. This high development and living standard can be mainly credited to the economic development of the northern regions, which were the first to industrialize and now boast impressive industrial, service, and financial sectors. Around half of all Italians live in the fertile and flat Po River Valley in the north, with the region of Lombardy housing nearly 10 million of Italy’s 60 million population. Milan is the beating heart of Lombardy and the North, and its economic prosperity unsurprisingly attracts Italians and immigrants alike in search of employment opportunities. It is a bastion of development and economic progress as the richest city in Italy and the fourth richest in Europe. This juxtaposition of poverty and wealth begs these questions: Who are these people who live on the streets of Milan, what are their stories, and what is Milan doing to help the welfare of its people?

The most visible display of homelessness is the sight of campouts and make-shift shelters on the streets. A 2018 census counted 587 people sleeping on the streets on a single night in February, marking an almost 100 person increase from the organization’s 2013 census. The majority of these people found shelter directly on the streets, while a minority sought cover in train stations, cars, busses, or hospitals. Within this population, 157 were counted in Municipio 1, the historic center of Milan. This may be attributed to the high housing cost in the area which may have priced residents out of their homes. Maybe yet, the street-sleepers were attracted by the heavy tourist traffic, relying on generous people passing by for a spare change.

In reality, people on the streets represent only a fraction of this problem; the total number of homeless people that night was 2,608 if also those in shelters are counted. This data concludes that a heartbreaking 2 in every 1000 Milanese do not have a home to call their own. Of those counted, 88% were men and 73% were non-Italians. It was also found that non-Italian homeless people averaged younger than Italian ones.

Foreigners make up a noticeably higher proportion of the homeless people in Milan compared to the rest of Italy, as a 2014 Italy-wide census of homelessness found 58.2% to be non-Italian. Paradoxically, this difference in proportion can be traced to the economic prosperity of Milan and Northern Italy, as hopeful immigrants are drawn in by employment prospects yet find themselves unable to make ends meet. The disproportionate trend of migrant homelessness is worrying, to say the least. The Borgen Project, a non-profit addressing worldwide poverty and hunger, concludes immigrants account for 90% of people living in Milanese slums. Though the 5 million foreign-born residents of Italy make up less than 10% of the Italian population, why are they disproportionately likely to be found among the homeless?

Migrant homelessness and poverty can be seen as a symptom of the insidious xenophobia that permeates Italy. Though laws are present preventing workplace discrimination and harassment for any reason, these laws don’t seem to herald the expected impact. Human rights consultant Luciano Scagliotti explains in a La Stampa article, “the Italian government has taken no action to address the long-standing systemic racial inequalities in the country… not even a discussion in the parliament has taken place. In part, this is because, in Italy, people pretend that racism doesn’t exist.” Some Italians simply harbor xenophobic sentiments, feeling threatened by growing ethnic minorities in an ethnically homogenous nation, especially following the numerous refugee crises.

Migrants in Italy seem to be confined to a few professions, with many people immigrating only to find their university degrees or professional experience from their home country to not be valid in Italy. Subsequently, many people are thus unable to find professional success and build skill-sets as they’re confined to menial labor that Italians don’t want to do. Some Italians don’t want to hire migrants for higher-up jobs, contributing to the 26.7% of immigrants in Italy living below the poverty line compared to only 6% of native Italians, following the COVID-19 pandemic. However, both native-Italians and foreign-born residents face poverty much harsher than the rest of the developed world.

On the surface level, homelessness does not seem much worse in Italy than in similar European nations, if not better. In an OECD* report of worldwide homelessness, Italy’s 2014 homeless population was recorded at 50,724 at a rate of .08% of the total population, a rate similar to that of Poland. This is in comparison to France’s 2012 homeless population of 141,500. Though Italy’s homelessness crisis does not seem as serious as other nations, a grim reality faces its poverty rate.

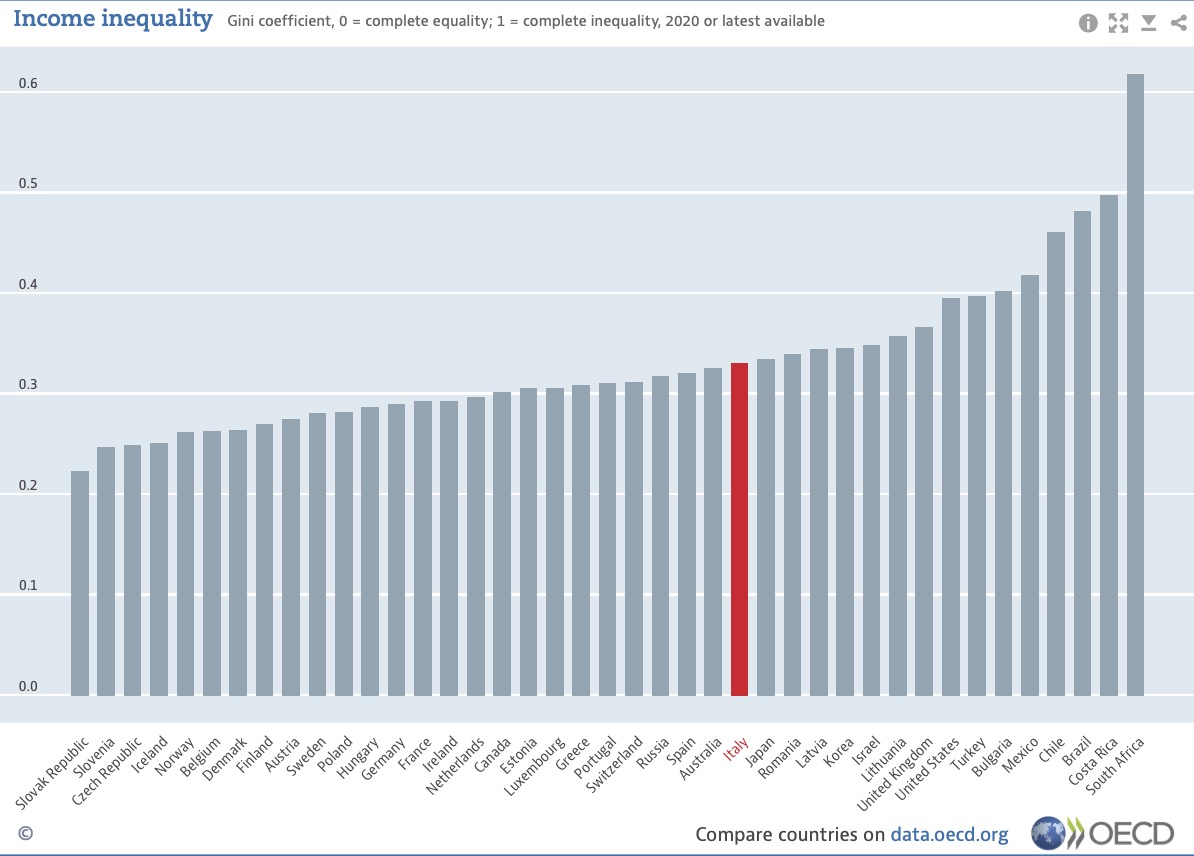

Another set of OECD data shows Italy’s poverty rate at 14.2%, ranking 7th highest in the EU and 3rd highest in the G7. Similarly, Italy has a Gini coefficient of .33 giving it the 6th highest income inequality in the EU. The most worrying statistic by far comes in the form of its poverty gap index of .396. The poverty gap is a ratio of the national mean income to the mean income of those living under the poverty line; basically showing how poor the poor are. Italy’s poverty gap ranks #1 out of every country listed on the OECD, and #3 worldwide just after Brazil and South Africa. Italy’s poor represent the poorest people in the developed world with respect to their nation’s average standard of living. There is not only a large wealth disparity between the rich and the poor but also between the poor and the ultra-poor. Numbers and indexes like these may be easy to brush away, but they represent real people who find themselves in difficult situations by no fault of their own. Though Italy’s development has brought riches to many people, it seems to have completely evaded more and left them in squander.

There is some hope in light of the harsh reality we face, as Milan and Italy are striving to improve inequality and homelessness alike. Milan hosts multiple shelters which help to provide support and aid for those in need, including a one-out of Centrale train station. This shelter has indoor space for 1,500 people to sleep as the weather becomes increasingly cold, as well as access to COVID-19 testing and safety measurements. The Comune di Milano also provides a service meant to combat dangerous freezing winter conditions whereby citizens and passersby can alert assistance workers of vulnerable homeless people on the streets. Furthermore, the ATS is resuming its campaign of vaccinating the homeless on the streets with services in Italian, English, French, Arabic, and Romanian.

The Italian government as a whole is taking large strides to combat inequalities threatening the welfare of its people. A €7 billion welfare program was passed in 2019 that allows qualifying households up to €6,000 in income supplement. With hopes to lift financial burdens on Italian families, this program however does not include non-EU citizens or those who have not been living in Italy lawfully for more than 10 years. The pandemic also saw Italy invest in other social welfare programs to lessen the economic blow, including €400 million to support food stamps and soup kitchens across Italy.

Poverty and homelessness remain one of humanity’s fundamental flaws and do not look to be going anywhere any time soon. Though Milan and Italy alike have their problems, hope is not lost and efforts are being made daily to bring people out of poverty and put roofs over their heads. You can help in this quest too, by calling the following number if you see a homeless person in need, especially in these cold winter months with COVID-19 cases on the rise again:

02 884 47646

Leave a Reply