Our generation’s specialty is making social media platforms rabbit holes of social comparison. They’ve become platforms displaying what we can now consider the perfect forms of our time. But these perfect forms aren’t limited to the epitomes of lifestyles and accomplishments. The obstacle today concerns mental health, exacerbated by laziness and ignorance.

It brings together the powerful force of belonging with a false sense of shared experiences.

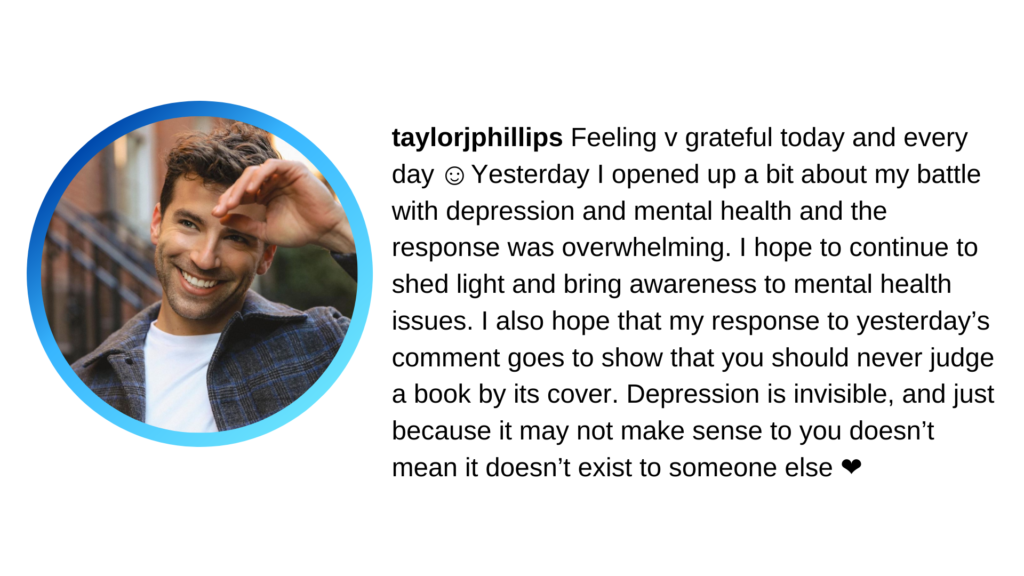

Social comparison doesn’t necessarily motivate us to hide or change things about ourselves. It can also prompt us to overshare with the intentions of honesty and authenticity.

And this is where things get concerning. Authenticity today is seen as this gold mine of content. TikTok is a platform that champions that kind of communication. Especially from an influencer’s point of view, being 100% yourself is what your followers crave, and it’s the most lucrative, fruitful source of content.

Influencers are an interesting case: you have individuals that have to be ‘on’ all the time. Live-streaming. Posting pictures. Posting stories. Collabs. Polls. Box-opening. It’s like every second of their day has a price. It’s a gruelling, revealing job. You lose all kinds of privacy, at times even peace of mind. They, luckily, speak openly about their mental health

But influencers’ mental health isn’t the issue here: it’s the impressionable kids and young adults who are living vicariously through them.

Depression, by definition, is known as “feelings of severe despondency and dejection.” Note the word severe here. A term that should deter excessive subjectivity is precisely abused in that manner.

Severe despondency means being deprived of hope and courage to an extreme extent. But what does ‘extreme’ mean? Well, we know that depression is debilitating for many. Depression, at its worst, can leave a person so debilitated that they can’t get out of bed, that they don’t shower or wash their dishes.

Still, mental health is a subject of spectrums, so thresholds are not easily delineated. And, that deprivation of hope and courage is nevertheless tricky to ascertain—it’s not always in clear view.

But am I wrong to insinuate that maybe everyone throwing around ‘depression‘ might not be anywhere near that point? In other words, aren’t most of these people technically self-diagnosing? Do they really know where they are on that spectrum?

Never would I have imagined that young people would talk about being depressed all over social media. And it’s almost like there’s a subconscious competition about it because, of course, one voice will eventually be joined by (too) many others.

If a small group of individuals with actual traumatic experiences that changed them share their stories openly, the group they’ve created is characterized by that. They are people who can accurately discuss depression. They can inform. However, the conversation inevitably becomes diluted—the sense of belongingness from outsiders ruins everything.

How? We’ve all seen the word ‘normalize‘ thrown around. It started after the amount of mental health content was increasing on the internet. That content brought an entire generation coming of age (and younger) to interact with it, to discuss all these new concepts together. Then, awareness continued to spread, which brought about normalization. This encouraged many to be unconditionally candid, to inform and recount of their experiences freely. An open space was thus created for others who found themselves in similar situations to openly share as well.

And that’s good. Bringing attention is essential; it’s vital. But we often overlook the fact that normalization itself can further contradict the progress made. It’s because normalization is more about knowledge accessibility than it is about teaching and informing.

Exponential awareness is not necessarily met with exponential understanding and sensibility.

It’s precisely the abundance of awareness that makes many unknowing individuals think they’re in the same boat when they’re really, well, on dry land. We think we know what boundaries are, but moderation is not a characteristic of our generation. And considering the fact that mental health is a series of gradients instead of defined thresholds, there is a significant issue at the core of discussing mental health. It’s too easy to self-diagnose.

It’s like a hypochondriac who Google’s symptoms. The worst condition is the first and final conclusion they make. To them, the internet says it, so it must be true.

Thus, an entire generation has based their self-awareness on a fabricated, misconstrued understanding of what mental health really is. Like I mentioned before, self-diagnosing is rampant. But the ultimately concerning part is that it’s simply a product of wanting to belong.

This isn’t like wanting to go to the gym for a hot girl summer or buying new clothes to change your aesthetic. It’s more than changing yourself; in fact, it’s changing a concept. It’s altering the definition of mental health, of depression, so you fit into it.

That sense of belongingness latches onto mental health and stretches to the extremes to cover anyone who thinks they’re included. With such an intense desire to belong, many of us subconsciously bypass our rational understandings of who we are to fit under that canopy. We like to feel a part of something, but our faces are always buried in screens, distracting us from thinking it all through. Some of us can critically engage, but many no longer can do this.

Here is a good TEd talk about this:

Many of us simply don’t know how to interact in a healthy way with social media. And that actually leads people to become depressed and anxious (with this study finding that more social media usage is linked to more perceived social isolation).

But I’m talking about this romanticization of depression; I’m talking about how unhealthy interaction with social media has misconstrued the elementary concepts of existence. I’m talking about people who mention depression like it’s a personality quirk.

We’re the same generation that demands those around us to use words correctly and effectively, yet here we are doing the opposite. The importance we have given depression and mental health has been damaged by our carelessness. Yes, it’s true, a lot of people suffer from depression, but that doesn’t mean it’s everyone.

If you’re having a bad day, unless diagnosed by a professional, you are not necessarily depressed. If you’re unhappy with the degree program you’re completing, again, you are not necessarily depressed.

Now we have children on social media platforms self-diagnosing themselves as depressed when many of them have no perception of what that word means. While there are undoubtedly people of all ages with the actual condition, with an estimated 10-20% of adolescents suffering from some kind of mental illness, it’s precisely them to suffer even more. They suffer at the hands of the internet’s inadvertent trivialization.

The visibility they’ve been waiting for has been shadowed by the unnecessary noise around the issue.

Of course, this is all by no means discrediting the condition or minimizing the symptoms or experiences. It’s precisely that reality that is being distorted.

Most of the normalization has contributed to that trivialization. While some may disagree, I can’t be the only one concerned that one day, in response to someone revealing that they are depressed, that we get an answer like this:

“Well, everyone is from time to time.”

When that reality is not necessarily or entirely true. And so the conversation we started will lose its inertia and progress.

If you are going through a tough time with your mental health, remember that there are resources for you! One great way to help yourself and others is to be informed. You’ll find links below to some TikTok accounts that have great explanations. Remember to never self-diagnose since only professionals can give you a solid answer to move forward.

Dr. Inna Kanevsky – a psychology professor who explains and debunks a lot of frequently cited mental health and psychology myths (among a lot of other kinds of content, she really posts a lot!)

Dr. Melissa Shepard – a psychiatrist & therapist who has good explanations of mental health subjects, including depression (this is her actual website)

Leave a Reply